A paper released during theSIGBOVIK 2024conference details an attempt to simulate theIBM ‘quantum utility’ experimenton a Commodore 64. The idea might seem preposterous - pitting a 40-year-old home computer against a device powered by127-Qubit ‘Eagle’quantum processing unit (QPU). However, the anonymous researcher(s) conclude that the ‘Qommodore 64’ performed faster, and more efficiently, thanIBM’s pride-and-joy, while being “decently accurate on this problem.”

At the beginning of the paper, the researchers admit that their ‘Qommodore 64’ project is “a joke,” but, sadly for IBM, its proof of quantum utility was also built upon shaky foundations, and the Qommodore 64 team came up with some convincing-lookingbenchmarks. There was some controversy about IBM’s claims at the time, and we are reminded it took just five days for the quantum experiment to besimulatedon an ordinaryMacBook M1 Prolaptop. The jokey Quantum Disadvantage paper (PDF link, headlining section starts at page 199) ports this experiment to a machine packing the far more humble MOS Technology 6510 processor.

To get deep into the weeds with the quantum theory and math behind the quantum utility experiment, please follow the above PDF link. However, to summarize, the C64-based experiment uses the sparse Pauli dynamics technique developed by Beguŝić, Hejazi, and Chan to approximate the behavior of ferromagnetic materials. Famously, IBM claimed such calculations were “too difficult to perform on a classical computer to an acceptable accuracy, using the leading approximation techniques,” recalls the paper. Not quite, and as already mentioned above, an ordinary laptop can obtain similar results.

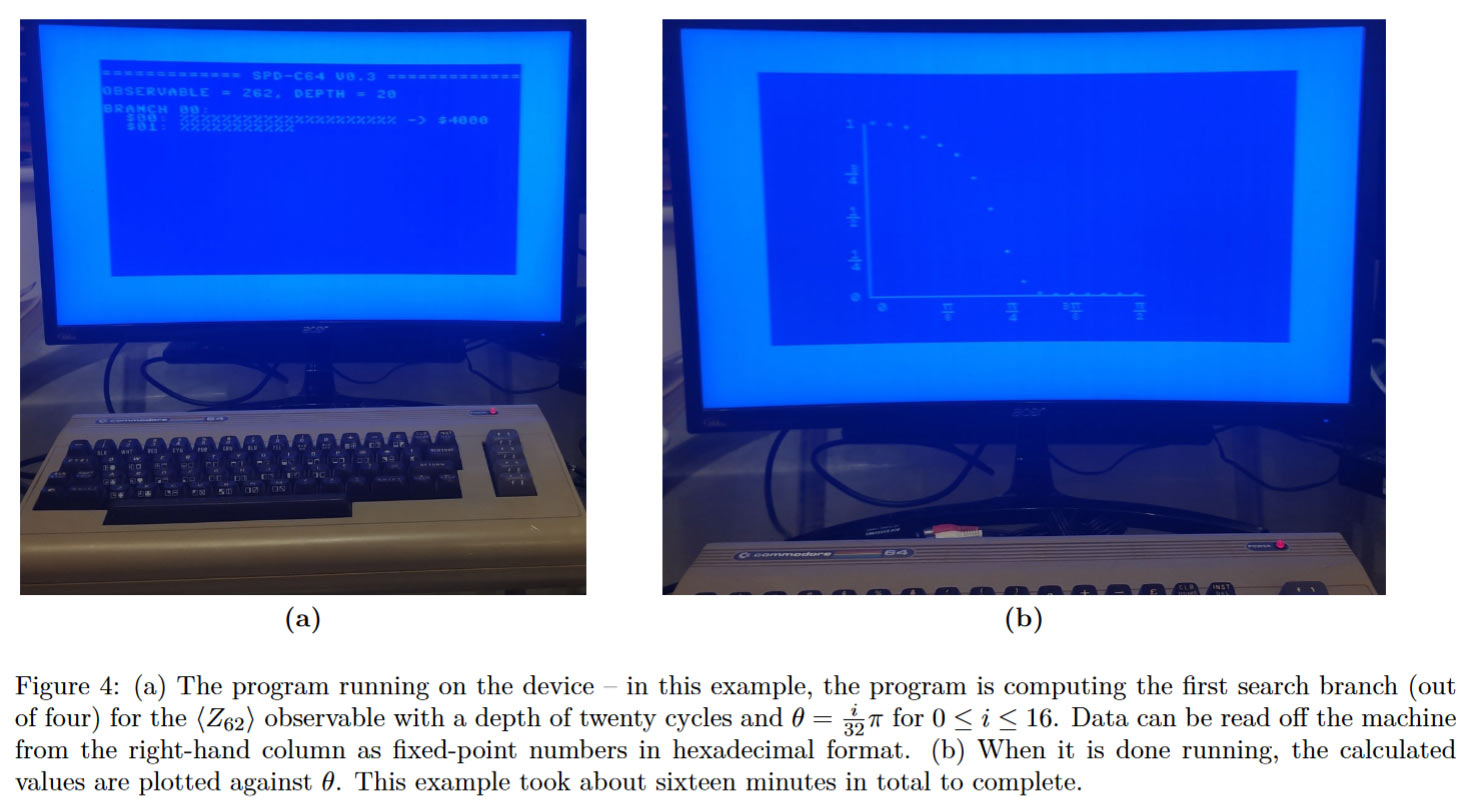

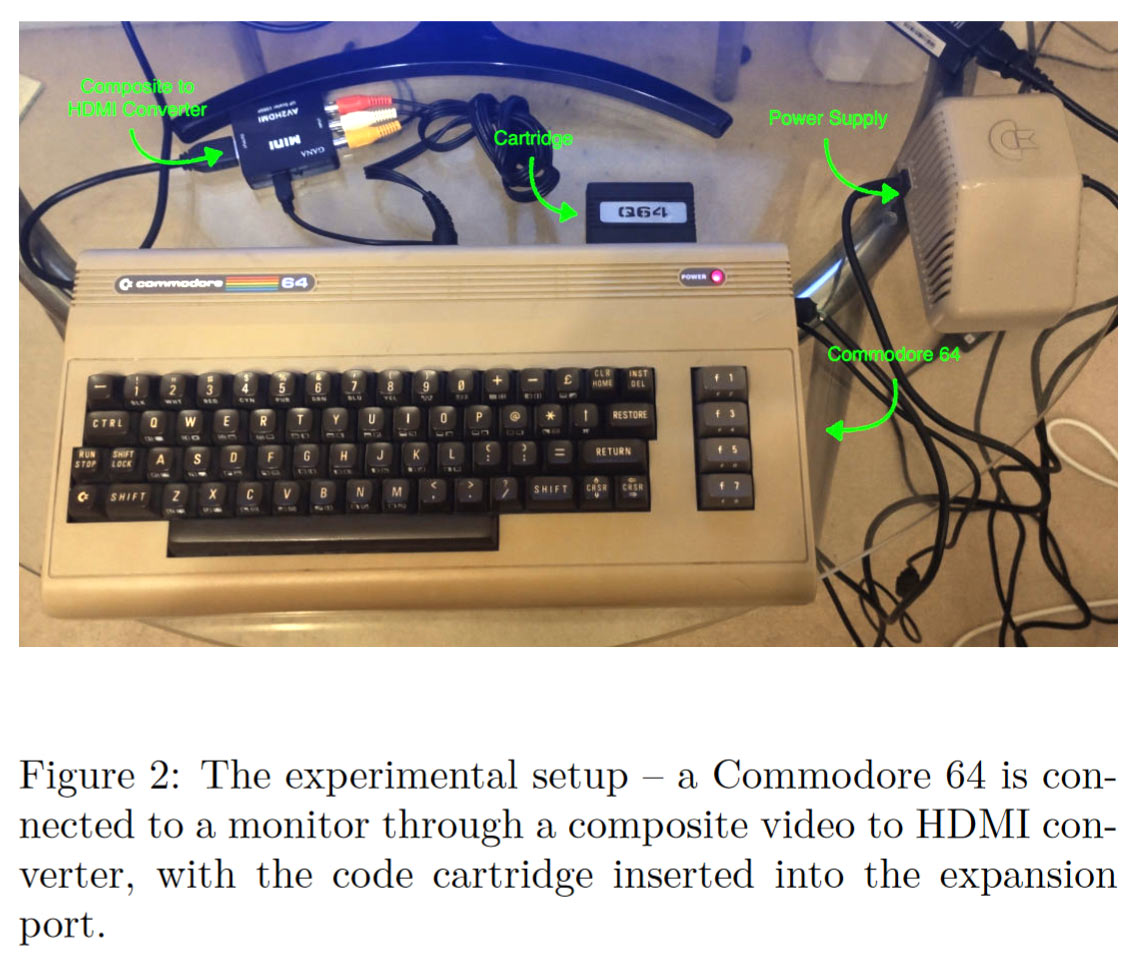

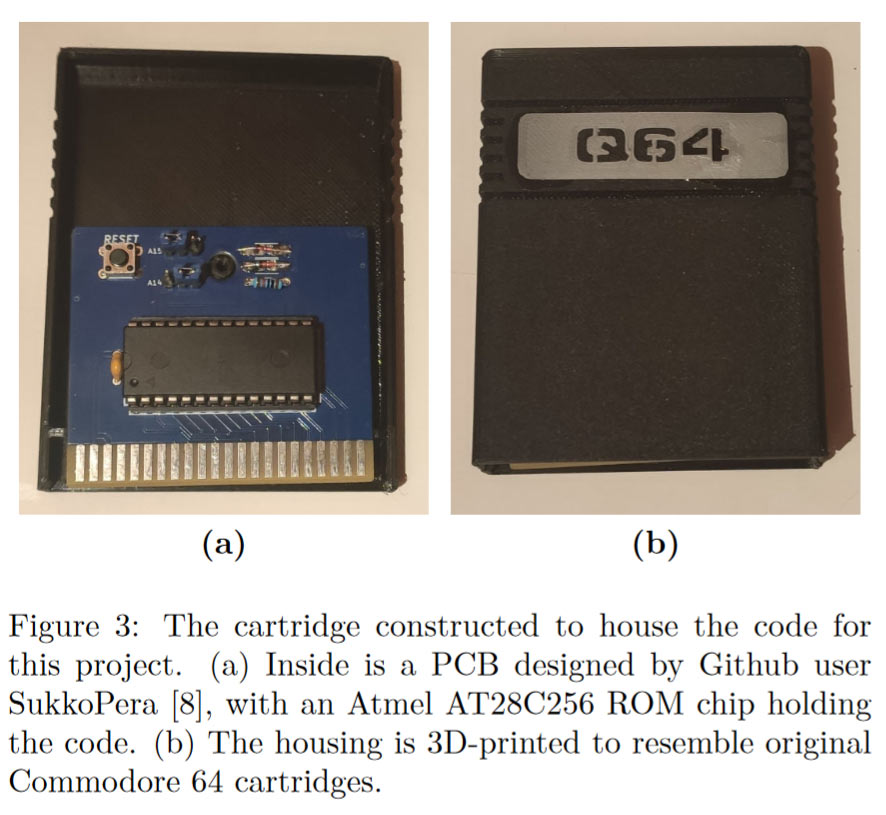

The anonymous C64 user(s) provide some interesting details of their quantum-defeating feat. Their aggressively truncated and shallow depth-first search model used just 15kB of the spacious 64kB available on theiconic Commodore machine. Meanwhile, the final code consisted of about 2,500 lines of 6502 assembly, stored on a cartridge that fitted in the C64’s expansion port. This code was handled by the mighty 1 MHz 8-bitMOS 6510 CPU. The C64 took approx 4 minutes per data point. (Testing the same code on a modern laptop achieved roughly 800μs per data point.)

In conclusion, the researcher(s) asserts that the ‘Qommodore 64’ is “faster than the quantum device datapoint-for-datapoint… it is much more energy efficient… and it is decently accurate on this problem.” On the topic of how applicable this research is to other quantum problems, it is snarkily suggested that “it probably won’t work on almost any other problem (but then again, neither do quantum computers right now).” Overall, it is difficult to know whether the results are entirely genuine, though a lot of detail is provided and the linked research references in the paper seem genuine.

We know many readers areretro computingenthusiasts, as well as DIYers and makers. So it is good to know that the author(s) of this paper say that they will provide source code to allow others to replicate their results. However, source code will only be supplied in one of three formats, they say: “a copy handwritten on papyrus, a slide-show of blurry screenshots recorded on a VHS tape, or that I dictate it to you personally over the phone.” So please add an extra pinch of salt to this story for that.

Get Tom’s Hardware’s best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Mark Tyson is a news editor at Tom’s Hardware. He enjoys covering the full breadth of PC tech; from business and semiconductor design to products approaching the edge of reason.